Rebels Without A Clock

by Michael C. Glab

IT'S A CHILLY October night in Iowa. The moon is nearly full and bright enough to cast shadows. Ken Mottet sits in the cab of his daddy's tractor, watching him and older brother Ray gather grain out in the field. Bored, he fiddles with the dial on the tractor's AM radio. The only thing it pulls in is WHO, out of Des Moines, a hard-core country-western station: Johnny Paycheck, George Jones. Mottet rolls his eyes. It's 1973, and he'd rather hear Mott the Hoople or Deep Purple.

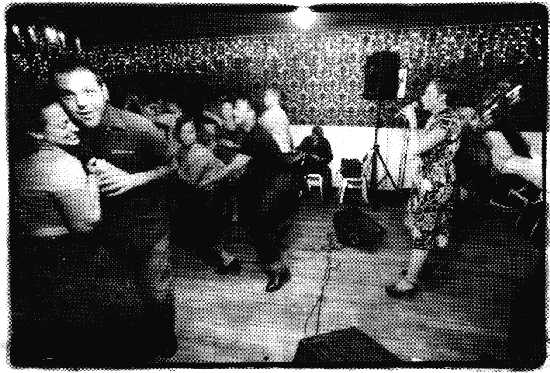

Fast-forward to April '2001. It's the Big C Jamboree, a monthly hoedown at Martyrs' on Lincoln Avenue. The Riptones, one of the oldest rockabilly bands in Chicago, will play a few numbers and then turn the stage to various combinations of players from established bands.

The place is packed. The men wear gabardine suits, bowling shirts, and cowboy-cut blazers, their hair sculpted into towering pompadours-"anvil-heads," they call themselves. The women wear skirts and angora sweaters and carry colorful vinyl clasp purses. Their cult worships at clubs like Schubas and Fitzgerald's, listening to bands like the Four Charms and the Honeybees.

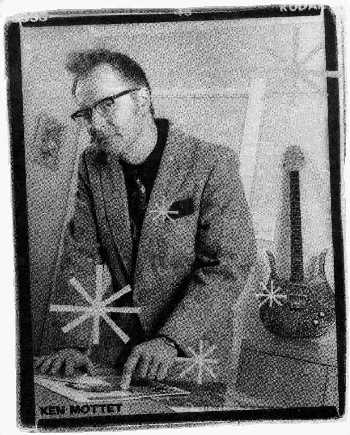

A thin fellow in a beige 1940s suit, with a notched-collar pastel shirt, bounds onstage and grabs the vintage microphone. "How ya doin', every-body?" With his deep, clear voice, he could be extolling the virtues of a low-mileage Rambler. "I'm Ken Monet." The introduction is hardly necessary, everyone knows him. He's the Mayor of Rockabilly.

Mottet and his wife, Mary Greene, are relaxing in the living room of their 1935 vintage moderne-style home in Berwyn. The late-winter sunlight streams in through 1940s-style bar-cloth drapes, giving the room a cool aqua tint. The Mottets are trying to find exactly the right words to define rockabilly.

"A three-piece thing," says Mary. "Stand-up bass, stand-up drummer, and a lead singer on guitar."

"The classic definition of rockabilly music is the marriage of white country music with black blues music," Mottet says. "It came together when Elvis Presley accidentally recorded his first record at Sun Studios in Memphis in the early 1950s. As the story goes, the musicians were fooling around with Arthur 'Big Boy' Crudup's song 'That's.All Right.' Sam Phillips, the owner of Sun Studios, stuck his head out of the control room window and said, 'What's that all about?' Someone answered, 'I don't know.' Phillips said, 'Whatever it is, keep doing it. That sounds like a hit record.' That, according to tradition, is when rockabilly started."

Rockabilly has another Genesis story, this one beginning with the late-40s act the Treniers. "The Treniers were playing jumped-up R & B stuff in a New Jersey club," says Mottet. "Bill Haley was down the street with his country-western band. Bill Haley came into the club where the Treniers were, heard them, and said, 'I gotta play me some of that stuff, too.' His band became the Comets, and they started playing 'Rock Around the Clock.'"

But according to Holler, the local rockabilly magazine Mary started two years ago, anvilheads also dig blues, jump, rock 'n' roll, swing, mountain music, and punk. So what is rockabilly? What motivates some 200 grown people in Chicago to buy all their clothing at Flashy Trash, Hubba-Hubba, Jazz Baby, Vintage Deluxe, the Kane County Flea Market, the Salvation Army thrift shop? To drive old Ford Fairlanes, to spin vinyl discs on restored Philco hi-fis, to decorate entire rooms in tiki motifs, to hide the VCR because it ruins the living room's Heywood-Wakefleld look?

Mottet's eyes light up. "JFK takes one to the head. Boom! It's over. November 1963. That's the end point of stuff I like. That's when America changes." Mary nods knowingly For them, any fashion, music, interior design, or automobile that came after that is tainted. Most anvilheads are squares. They don't take ecstasy, they don't trade sex partners. They get married, buy homes, raise kids, throw barbecues. Rockabilly is a fantasy, a nostalgia for more innocent times. For anvilheads, it's a way of life.

It's Country Music Holiday, the monthly Sunday-night country-western jam session. Mary Mottet is greeted by Laurie, a blond woman wearing horn-rimmed glasses, a checked shirt, and rolled-up blue jeans, looking like something out of State Fair.

Mary has a present for Laurie: a mint-condition doll with blindingly blond hair and a billowing pink dress. "Where'd you get it?" Laurie asks.

"At an estate sale in Berwyn this afternoon."

Neither Laurie's clothes nor her home is typical for Bridgeport. "Where I live, when my boyfriend and I are walking down the street, somebody has to ask if we're going to a costume parts" she says. "But when I come out with these people, I feel like the bumblebee girl in that Blind Melon video: I don't feel so strange anymore."

"I was born January 31, 1961," says Ken Mottet. "Three years to the day after America launched its first satellite into outer space, four months before Alan Shepard went into space."

Mary rolls her eyes and laughs. "My husband," she says. "I love him."

It's a Sunday night in 1973. Mottet is lying on the living room floor watching NBC's historic satellite broadcast Elvis: Aloha From Hawaii. "Here's this big drug-addled goofball in a white jumpsuit with bell-bottoms the size of sails, and his goofy-assed band," Mottet says. "But when Elvis Aaron Presley walked onto that stage I was mesmerized. Every move was a picture. Every nuance, every blink, every wave, every step was poetry. The guy nailed me. At that time, I had long blond hair, big aviator glasses, polyester shirt, bell-bottom Levi's, and Frye boots. I was completely Mr. 70s. All I listened to on the radio was Top 40 stuff. It wasn't enough. So I started listening to Elvis records. If you were lucky and did your research, which I did, you got led back to the Sun sessions records, the hard-core hiulbilly-rockabilly stuff. Somehow that led me to grabbing a Gene Vincent record. That, in turn, led me to grabbing an Eddie Cochran record."

Fairfield, Iowa, bad only one high school, and most of the kids who attended it lived nearby, but Mottet had to travel 13 miles. Like the other farm kids, he was branded an outsider. "I was a complete loser," he recalls. "I was the egghead. I was a straight-A student and a theater pussy. I was in the speech club and the science fiction club."

On graduation day he gave the valedictory address, reminding the assembled faculty, the graduates, and their parents that Fairfield High was built during the Depression by WPA labor. "I'm very proud of that," he said. He assumed that most of his class-mates were tittering, but he didn't care. A decade later, attending his ten-year reunion, he wondered if his old classmates would still think him a doofus. Instead, he says, a lot of 'them rushed to shake his hand. "So many of them said to me, 'We thought you were so cool because you were your own person.' In the back of my head I was thinking, 'Why the hell didn't you say something to me then, when I needed it?"'

After his two older sisters went off to college, he and his brother Ray got their own bedrooms. They slept each night with their doors open, sharing the AM radio next to Ray's bed. They'd listen to KIOA-Des Moines' Top 40 station-or KAAY out of Little Rock. On clear nights they might pull in WLS. Like a million farm boys before him, Ken began to dream of the big city.

KMCD in Fairfield had a tradition of hiring a high school student to host its evening show, and at 15, Mottet started working the 5 to 10 PM shift. "For five hours a night, I was the voice of Fairfield. 1 would get out of school at three o'clock, walk uptown, have dinner at the Broadway Grill, go to work, and get off at ten. My dad would drive into town every night, pick me up, and drive me home. It was the best job a kid could ask for. We played stuff off the Grease sound track, 'Y.M.C.A.,' Helen Reddy's 'I Am Woman.' I would go digging into the record library and pull out Beatles and Beach Boys 45s."

Mottet stayed at KMCD for two years, and as a freshman at the University of Iowa he landed a job as a DJ at KXIC AM, a Top 40 station in Iowa City. Itís FM sister station played classic rock, so occasionally he'd thumb through its record library. "I pulled out the Stray Cats' very first English record. Brian Setzer looked like he was about 12 years old. The FM station was never going to play it so I took it home and put it on. It changed my whole goddamned life! The Stray Cats grabbed me by the throat and would not let go. It was because of that record, because of the pictures on the inside of the record cover of the band done up in pink-and-black suits and leather jackets that said 'Leopard Man' and they're all wearing giant pompadours, that I went public. Before that I'd been Mr. New Wave: skinny ties and shark-skin jackets with black Levi's and white deck shoes, with a mullet haircut. When I got ahold of that Stray Cats record, I put it on my turntable and didn't take it off for maybe two months."

Soon afterward Big Daddy Sun and the Outer Planets, a rockabilly band from central Illinois, came through Iowa City, and Mottet pinned up his hair into a makeshift pompadour for his first outing into the rockabilly world. "They came on like gang-busters," he remembers. "They were a five-piece band with a rhythm guitarist, Urban Dim, who had a bright red pompadour that was 18 inches of flame on the top of his head. They were the Johnny Appleseed of rockabilly in the midwest. Whenever they would come back to a city they'd played before, there'd be guys in the audience who'd since grown pompadours and started bands."

In Iowa City, Mottet also tried to become a stand-up comedian. He performed at open mikes and scratched around for work in bars and comedy clubs, making "ten bucks here and ten bucks there" but not enough to support himself. On his upper arm he wears a tattoo of a goateed man. "Lenny Bruce," he says. "It's rather badly done, and people usually think it's Merle Haggard." As a kid he'd worn out records by George Carlin and Bill Cosby "I can recite Cosby's records chapter and verse," he says. "Ask me to do 'Chicken Heart.' That was where I first got the comedy bug, off those guys." But he never got anywhere with comedy. "I have no self-esteem as a performer I'm convinced everybody hates me and wishes I were dead and that I'm just an annoyance. I do not accept rejection well."

After earning a degree in theater arts, Mottet got a job at a pizza parlor in Iowa City. The next year, when Big Daddy Sun and the Outer Planets hit Iowa City again, Mottet and his girlfriend, Trixie, struck up a conversation with lead singer Ron Cannon, who invited them to tag along to Chicago for the band's record release party at the Cubby Bear. "It was the first time I'd seen real live rockabilly onstage and in the audience at the same time," Mottet says. "Giant pompadours, old gabardine shirts, baggy pants, two-tone shoes, guys with tattoos up one arm and down the other. I felt like I had come home. I remember standing just inside the front door of the Cubby Bear, looking over my left shoulder and seeing all these cool guys watching the band and looking over my right shoulder and seeing Wrigley Field. I started thinking, 'I can live here."'

By the end of the year he was sleeping on the floor of Cannon's apartment while he and a friend looked for a place of their own. But before moving to Chicago, Mottet visited an Iowa City barbershop and asked for a pompadour. "To this day, I can recall sitting in that barber chair and seeing Trixie with tears in her eyes. She eventually followed me into rockabilly. I have not stopped putting grease into my hair and wearing pink-and-black jackets and two-tone shoes since that day in 1981."

In Chicago, Mottet flipped dough for a pizza joint in Norridge and tried his luck in the comedy clubs again. "This was during the comedy boom of the early 80s," he says. "I made appearances at the Chicago Comedy Showcase, Who's on First, Zanies, the Comedy Womb-the circuit. But I just never got the head of steam necessary to make it happen. I didn't know how to promote myself, and I never got beyond the open-mike stage." In the summer of 1985 he took a job as a VJ at a UHF station in Alaska that played music videos 24 hours a day, but he was homesick. After moving back the following summer he took a job as a shipping and receiving manager at a north suburban music store, where he's worked ever since.

Mottet's rise to the mayoralty of Chicago's rockabilly scene began in 1993, when Gabrielle Sutton asked him to emcee her monthly Big C Jamboree at Batteries Not included. He soon parlayed the gig into emcee appearances at rockabilly shows all around town. "One night in 1997 I went to see the Fire-flies at Club Lower Links," Mottet .says. "There were maybe three people in the crowd. Steve Szczeblowski, guitarist for the Fireflies, being a clown, pointed me out and introduced me to the crowd as 'the Mayor of Rockabilly, Ken Mottet.' It grew from there." Soon Mottet began introducing him-self as the Mayor of Rockabilly at shows. And in addition to his emcee gigs, he hosts his own cable-access music-video program, The Other Side, which he describes as "an amalgam of musical styles. It's what I think an intelligent music fan's record collection should look like: Dead Kennedys, the Ramones, Black Oak Arkansas, Tony Bennett, Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, and Incubus. It's everywhere at once. It's the music show I've always wanted to watch."

For someone who could never promote himself Mottet never seems to have much trouble promoting the rockabilly scene. "I know everybody by name," he says. "When I was growing up, my dad could talk to anybody, and he knew everybody I've always admired that. I'm trying to pick up on that tradition. I'm a show-business kind of guy I can stand behind a microphone and go blah blah blah for hours on end. I am slowly stumbling into show business. I might actually make it before I die."

In late January when Mottet turned 40, Mary took him to the Grand Ole Opry. The two caught a Saturday night show at the Ryman Auditorium, a historic palace in downtown Nashville, far from the suburban tourist trap Opryland. The Opry began at the Ryman, broadcasting its Sunday evening program across the nation. Says Mottet: "It was like goin' to church."

He wore a special dark green sharkskin cowboy suit he'd bought a few years before at Gabrielle Sutton's Vintage DeLuxe shop on Belmont. Sewn into the lining of the jacket was a label reading "Expressly tailored for Mr. Bill Anderson." Mottet couldn't believe his eyes when he plucked the suit off the rack. A DJ, songwriter, and performer, Whispering Bill Anderson is a legend in country music, having served as the unofficial host of the Opry for as long as anyone can remember. As it happened, Anderson was closing the show at the Ryman the night Ken and Mary attended. Afterward, Mottet dashed around to the stage door and waited, chewing the fat with Eddie Stubbs of WSM. (On a clear night you can pick up WSM out of Nashville and hear some honest-to-God country; Mottet often catches Stubbs's evening show on his car radio as he drives home from work.)

Somehow word got back to Bill Anderson that someone wearing one of his old suits was waiting outside. Anderson met Mottet at the stage door and looked at the sharkskin suit. "Where'd you get this?" he asked. Mottet told him; "What a journey it must have had." He autographed the suit and posed for pictures with Mottet.

Mottet still swoons as he tells the story. "When Whispering Bill Anderson said, 'Where'd you get this?' that's all I needed to hear."

Mary Greene grew up in the Austin neighborhood, playing jacks and double Dutch with her girlfriends in the alley be-hind her home. Her mother worked in a Ford dealer's office, and her father was a telephone installer. They sent Mary to Saint Thomas Aquinas grade school.

Mary didn't listen to the radio much. "I was out jumping rope," she explains. "We were always outside." Occasionally she'd hear her older sister Kathy, a cheerleader, playing "Yummy Yummy Yummy" by the Ohio Express or "Incense and Peppermints" by the Strawberry Alarm Clock.

In 1966 a black family moved in down the block. Mary made friends with the new family's little girl, but as the two jumped rope and played kickball, the other families on the block were contacting real estate agents. Within two years her neighborhood was completely black. "My parents were like blue-collar intellectuals. They refused to be part of white flight, so we stayed." Mary's mother had been raised in the house, the family had hung on to it through the Depression, and the part that belonged to Mary's grandmother hadn't changed since 1926. "We were pretty much the last white family left in the neighborhood. I was the only white kid left in my grade."

Mary was comfortable enough, but in April 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the neighborhood went up in flames. "Here I am, seven years old, walking down Madison Street, and I hear all this noise. People were dragging things out of storefronts." Still her family refused to sell. Only after Mary's grandmother died in 1973 did they move to Riverside. "We went from a neighborhood of complete poverty to one of complete affluence-but our finances didn't change a bit."

As a child she'd seen performance footage of Buddy Holly and Bill Haley and His Comets on TV "I was intrigued by Bill Haley's big fat grin and his style. The band members were jumping all around and flinging themselves all over the stage." Her parents played Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, and Nat "King" Cole on their iridescent green Webcor record changer (which Mary still has).

One of her favorite dresses was a relic from the Eisenhower era. "It was that strange, unique pastel color combination that you only saw in the 80ís. Pale brown, pastel orange and pink and aqua, maybe a little chartreuse in there. Every imaginable ugly old color in a seersucker dress with crinoline. I wore it proudly to school. And then I got laughed out of the place."

She wore her grandmother's fur stole and her mother's black satin dress with white polka dots and a huge swing skirt. "Everybody else was wearing Earth Shoes." She began shopping at vintage stores when she was 19, around the time she started going to clubs. One night in 1981 she heard the Elvis Brothers at Tuts, at Belmont and Sheffield. "I pretty much thought that was the livin' end." In her early 20s, after moving back to the city, she discovered Hi-Fi & the Roadburners and began dating lead guitarist Carl. Schreiber, who wore a stratospheric pompadour. She listened to bands like the Greaseballs, the Deacons, the Rebel Rousers, the Stray Cats, and Johnny Reno and the Sax-maniacs. She became friendly with Gabrielle Hernes (later Sutton), whose rockabilly night featured area bands like the Moondogs, Rockin' Billy & the Wild Coyotes, the Chasers, the Three Blue Teardrops, the Riptones, and Hi-Fi.

By the early 90s the retro-rockabilly scene was becoming entrenched. At that time the anvilheads were divided into two camps: the gabardines and the blue-collars. Gabardines like Ken Mottet woree suits and ties and danced precisely. Blue-collars like Mary Greene wore leather jackets and tucked cigarettes behind their ears. Both groups attended the same shows and shopped at the same vintage stores, but there seemed to be an invisible line between them. Ken and Mary had both been immersed in rockabilly for years, but as late as 1993 they didn't know each other's names. She'd see him at a show and roll her eyes: "Oh yeah, here's the funny comedy guy with the glasses again."

They met finally at a barn dance given by Ranger Tod, singer for the Riptones, on a farm near Saint Charles. Tod, who'd earned his nickname as an Illinois park ranger, was famed for his barn dances. "He'd push all the machinery out of the way, set up a stage, put in a PA, and the Riptones and anybody else who showed up would play," says Mottet. "He'd have a big bonfire going with people roasting marshmallows. The jam sessions would last late into the night, there'd be camping out, and the next morning there'd be a home-cooked breakfast on Ranger Tod's front porch."

Mary wore a new dress, a white square-dance number decorated with musical notes. Ken wore a blue gabardine jacket with a red shirt. "He walked up to me, looked me in the eye, shook my hand, and said, 'Hi, I'm Ken Mottet. I think it's about time we meet.' As he held my hand, I looked him in the eye and it was like everything else in the room disappeared. I went, 'Oh my God!' and knew that I was going to marry him." "I don't remember that moment at all," Mottet says.

Four years later they were married. They held their reception at the Major Hall, a tavern on Grand near Central. Their guests ate off plates made of Melmac, a futuristic-looking nonbreakable material that was briefly popular in the early 60s, and danced to the Riptones. The couple honeymooned at Niagara Falls.

If the Mottets have anything to do with it, Berwyn will become the next rockabilly hot spot in the Chicago area. Berwyn is full of 1920s bungalows that still have their original leaded windows, glass doorknobs, and wood trim. Yet home is wherever two or more anvilheads, 'billies, or retromaniacs gather.

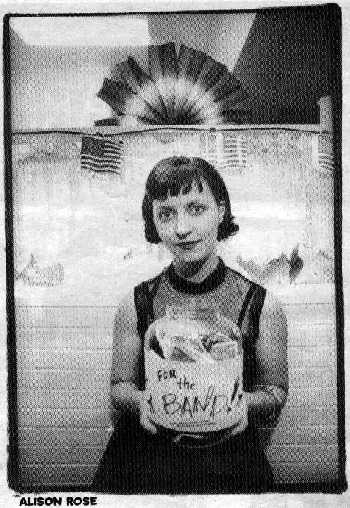

"If I hadn't found these people, I would probably be renting movies and sitting at home," says Barbara Clifford, lead singer of the Honeybees. On a typical day she looks like Debbie Reynolds in one of the Tammy movies, wearing cuffed blue jeans and a work shirt knotted at the waist. "The rockabilly style represents a time of fun," she says. "It's a good look. It makes women look beautiful.' What girl doesn't want to be a pinup girl? What girl doesn't want to be a prom queen?" Her roommate, Susan Funk, wandered into one of the Big C Jamborees about five years ago; now she wears nothing but vintage clothes, and her home is done up in art deco. "People sometimes say, 'What, are you stuck in the 40s or 50s?' We just like the style. The textbook definition of rockabilly is a musical form that was popular between 1955 and 1963. But for me it was a lifestyle." Mary Mottet, who's spent the last decade in advertising, started Holler magazine, the local rockabily bible, in 1999, and last year she handed it off to Clifford and Funk.

Holler keeps the anvillieads up to date on flea markets, antique shows, bands, and rockabilly conventions. It features how-tos on haircuts and rolling your jeans, interviews with artists, record and film reviews. Each issue coincides with the Big C Jamboree. The March issue included obituaries for Dale Evans, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, and big-band leader Les Brown.

"This isn't just the 50's or Sha Na Na," says Mary. "It's the 30s and 40s, Texas swing, Bessie Smith, or some farmer who made one record 55 years ago. It's the heartland." "This all starts out as a collection of affectations," says Mottet. "But if you stick with those affectations long enough, they become real."

The Big C Jamboree is in full swing. From the moment the Riptones' lead guitarist hit his first chord, the dance floor has been jammed. Couples rock and twirl, their steps precise, their carriage erect, their hair and makeup artfully tended.

The Riptones' bassist, Earl Carter, has slicked-back hair exposing a widow's peak and stiletto sideburns that reach all the way to his chin. With an occasional toss of his head, he flips a shiny tendril of hair out of his eyes. The sleeves of his denim work shirt are cut off at the shoulders, exposing beefy arms with matching Bettie Page tattoos.

"I've lived in Chicago on and off since 1984," says Ken Mottet. "One day I found myself standing in a tuxedo with my best friends in the back of a big-ass church in Chicago, getting married to the woman I want to be buried next to. Sitting in these pews are guys in broad-shouldered suits with their hair slicked back, and the women are all dressed up like Evita. I thought, 'Goddamn it, I live here. This is my home. These are my friends.' The thing I love most in life is friendship-more than the shoes, the painted-leather jackets, the records. I can go to a show at the Metro and walk through that crowd and people are patting me on the back-'Hey Ken, how's it going? Where's Mary? Paul and Ann Marie are here.' That's the best goddamn feeling in the whole world."