The Onion

Nashville

Scene

(Issue Date: Sept. 10th, 1998)

True Believer

Feathers almost achieved recognition

By Randy Fox and Jim Ridley

In the months before his death on Aug. 30, Charlie Feathers seemed

poised to receive the credit he was due. It wasn't the first time

recognition seemed at hand for Feathers. But with the recent resurgence of

interest in rockabilly, and with the release of a classy two-CD Feathers

retrospective on Revenant Records, acknowledgment finally seemed at hand.

Even in periods of deep obscurity, Charlie Feathers always

recognized his importance to American music, and he didn't mind telling

people. The stories he spun often contradicted commonly held memories and

facts: Feathers himself often said that he was playing rockabilly as early

as 1949 and that he taught Elvis how to sing rockabilly. As a result, some

people characterized him as a nut, a could-have-been--a musical eccentric

who sought to disguise his lack of success with inflated tales. But

whatever his reputation, his music speaks for itself.

Like the army of poor, white, Southern boys that revolutionized

American music in the '50s, Charlie Feathers was born into a world of

poverty so severe that it made little differentiation between white and

black. Born near Slayden, Miss., in 1932, Feathers left school after the

third grade to work in cotton fields and at other hard labor. He learned to

play guitar from bluesman Junior Kimbrough, but his first musical hero was

Bill Monroe, followed soon by Hank Williams. All of these influences, and

others, eventually shaped Feathers' style.

By 1949, Feathers was living in Memphis, and he began hanging around

the Sun Studio shortly after it opened in the early '50s--recording demos,

working on arrangements, and cowriting songs, including "I Forgot to

Remember to Forget," Elvis' last Sun single. In 1954 and 1955, Feathers

recorded a handful of powerful, soulful hillbilly songs for Sun--songs that

caused Sam Phillips to refer to him as "the first great country singer I

ever cut and probably the best."

But Feathers' heart, it seemed, lay in rockabilly. In 1956, the singer

had two rockabilly songs he was itching to record. Although Phillips

refused to release any rockabilly sides by Feathers, Lester Bihari at

Meteor Records, Sun's main competition in Memphis, was more than happy to.

The resulting single, "Tongue-Tied Jill," backed with "Get With It," became

the singer's first classic rockabilly release. The record didn't gain much

exposure outside Memphis, but it led to a deal with King Records in

Cincinnati.

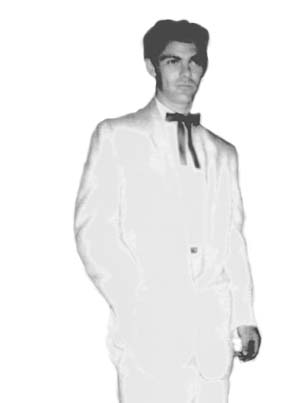

Original master Charlie Feathers, a rockabilly singer to the end. Photo courtesy of Richard Weizer

The four singles Feathers recorded for King in '56 and '57 sold few copies, but they are some of the purest, most unadulterated rock 'n' roll ever recorded. At heart, rockabilly wasn't clean, fun music--it was a mutant hybrid of the hot hillbilly boogie and over-the-top rhythm and blues of the late '40s and early '50s. It was midwifed not by the teen scene, but by young, hotshot crackers in honky-tonks and dives all over the South. A case in point is the King side "Bottle to the Baby," on which Charlie Feathers sang frantically about having to feed his infant before a night of carousing.

As the popularity of rockabilly faded and most of its early proponents moved toward pop or mainstream country, Charlie Feathers kept the spark alive--recording a handful of singles on obscure labels and slugging it out in the honky-tonks of Memphis. When the first rockabilly revival began to stir in the '70s, Charlie Feathers didn't have to return to the music: He'd been standing his ground for years.

The recordings Charlie Feathers left behind--studio, live, and dozens of home demos--reveal a soulful passion and a stubborn adherence to his distinct musical voice. This single-mindedness may have denied him wealth or success, but it's also what made him such a great performer.

Over the years, Feathers would receive smatterings of recognition. He was featured in Peter Guralnick's 1979 book Lost Highway, and his belated major-label debut came in 1990 as part of Elektra/Nonesuch's American Explorers series. Yet even as he became recognized and hailed as an American original, his reputation for eccentricity and spinning tales continued to eclipse his music.

One of the best Charlie Feathers stories dates back to 1974: On his first trip to the West Coast, he recorded a single for Rockin' Ronnie Weiser's Rollin' Rock label. After spending most of the day working on one song, Weiser reminded Feathers that they needed another song and asked for something a little hotter. Feathers promptly grabbed a bass and slapped out "That Certain Female," three minutes of powerful, unrestrained, rockabilly madness--illustrating just how simple it could be for him to produce a classic.

It's doubtful that all of the stories Charlie Feathers told about himself were true. But regardless of their veracity, they remind us that the truth may not always be as simple as we believe it to be. The history of American music has largely chosen to ignore Charlie Feathers' accomplishments, but the fact that Charlie Feathers lived that history cannot be denied.

--Randy Fox